|

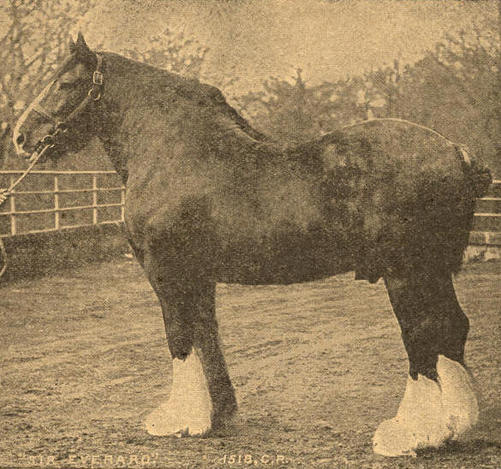

The Suffolk Punch will keep the road, The Percheron goes gay; The Shire will lean against his load All through the longest day; But where the plough-land meets the heather And the earth from sky divides, Through the misty Northern weather Stepping two and two together, All fire and feather, Come the Clydes! - Will Ogilvie  Gwyneth, one of our registered mares, at pasture. Gwyneth, one of our registered mares, at pasture. I am blessed in recent years to be sharing my life with the most magnificent of the heavy horses, indeed with one of the most splendid creatures ever to grace this earth: the Clydesdale horse. More, I have had the double blessing to share many a working day with them – training, ploughing, discing, harrowing, haying, hauling, and sometimes, doing my bit to teach others to do the same. The Clydesdale horse originated in the Clyde River valley of Scotland, at least in ancestral form. The Clydesdale of the modern era is a mixed bag, however, the most so of all the heavy horse breeds. Herein lies its versatility, say some. While there are more powerful horses for working the furrow alone, or for taking to pulling contests, none is better for more jobs than the Clyde. Their breed standard calls for the ideal of substance without coarseness; neither grossness nor bulk, but rather quality and weight. An apt description, a person is led to think, while one is there in front of you.  Seeding Canadian peas with four abreast of our Thompson Small Farm Clydesdales. Seeding Canadian peas with four abreast of our Thompson Small Farm Clydesdales. If you ever were to hitch a Clydesdale with a Percheron or Belgian and make off down the road, you might note that the others take almost two strides for every one of the Clyde. This is a function of build. The Clyde has the long cannon bones and high rump of a nomad, albeit a very powerful one, the other two are “shorter coupled,’ having shorter bones combined with a hugeness of mass that can indeed be aptly described as coarse by comparison. This makes the other two very powerful, but comparatively slow. I well remember three days I spent mowing hay with Skeeter Thurston, an ex-pat Nebraskan, on his ranch north of Elmira. He was one of the rare ones, and I’ve known a few of them here in Alberta, who believed us foolish to entirely turn our backs on the old, millennia proven ways, and lived their beliefs. We hitched our teams to McCormick-Deering Number Nine machines, the Cadillac of the old horse-drawn mowers, these ones with six foot sickle bars; he with his team of American Belgians and me with a team of our Clydes. He instructed me to lead off, and away we went around that relentlessly hilly quarter under the late August sun, traces jingling and knives whirring, but never making such a racket that the call of the Meadowlark was lost to us, nor so obtrusive as to scare away the sentinel hawks bent on the mice we would stir. By the time we’d made a circuit, my Clydesdales and I were no longer in front of Skeeter, we were coming up behind him. Skeeter suggested that my horses were in better shape than his that summer, but it is also true that it is this quality of covering ground that prompted one old Clyde breeder of Saskatchewan whom I got to know a little while making use one of his stallions to quip in good-humored rivalry, “Sure the Belgian can haul a little more of a load. Me, I prefer to use a Clyde and actually get the job done!” It is this same quality of a long, smooth stride that made them ideal for road and town work, and today, for riding.  "Bay-with-four-whites" Clydesdale. An excellent example of the breed. "Bay-with-four-whites" Clydesdale. An excellent example of the breed. It is said that the demise of the horse era heralded a new age in which horses were, on average, treated much better. I suppose this is true, for those horses that weren’t turned into dog-food, and there were literally millions of them that met this fate. (Although I suppose, really, it was not so much the dog but the tractor that ate them.) In more recent decades, the heavy horse has made a minor comeback, although I fear that forces may again be turning against them. In fact, although the Clydesdale horse is probably the best known of the heavy horse breeds on this continent today, thanks in large part to the advertisements of the Budweiser beer company, it is ironically also one of the rarer ones, and is under watch by various Rare Breeds societies. Aside from a precipitous drop in numbers early in the 20th Century, the end of the horse era created some other issues for the Clydesdale. When they were being bred for the farm, the colour of the horse took a back seat to quality. The Clydesdale evolved as a colourful, even flashy horse. The best ones tend heavily towards roaning, which in this breed is actually more of a bold marbling and splotching, than it is the subtler overall wash of flecking called “roan” in other breeds. Against a background of just about any colour a Clydesdale horse can be overlaid in a liberal splashing of white, with the white predominating in extreme cases. It is these roan horses that carry the quality genes in this breed. One second-generation Clydesdale breeder of renown assured me that if you take the top ten Clydesdales at any show where true quality is the concern, eight of them will be roans or have a strong lineage of roaning. Yet today with the Clydesdale, we see a trend towards uniformity – solid bay with four white feet, or “four whites,” as seen in the Budweiser hitches. While there are many fine bay Clydesdales (left), quality will suffer if this is what you are breeding for alone in this horse. Worse for the breed has been the fashion towards black Clydesdales (with the signature four whites and facial blazes, of course.) One colour that is rare in a Clydesdale is black, and it is hard to breed one of real quality.  Sarah, a "blue-roan" daughter of Emma, in wolf-willows. Sarah, a "blue-roan" daughter of Emma, in wolf-willows. But worst of all for the quality of this breed has been the modern trend that is affecting all heavy breeds to produce an excessively tall, lanky animal with less muscle – again, an animal of poor quality. While the Clydesdale is leggy for a heavy-horse, it is meant to be subtly so. But now we see a case of fashion over function predominating in many show rings. Some very strange looking ‘work’ horses have been the result, and it is no exaggeration to say that some of them are tending more towards huge, mutant track horses than otherwise. I see this as a trend driven by distinctly urban sensibilities, rather than rural ones that were the genesis behind these breeds. We’ve seen this with many dog breeds as well, the impetus being towards producing attractive nitwits. The trend mirrors our own human trajectory with the sweeping move away from the land we’ve experienced in recent decades. The less useful we become ourselves and to ourselves, the less useful we expect our animals to be. The danger here being that when the day returns that demands a general competence of us, we will have lost all ability to meet these demands. And so will have our animals.  The result of poor breeding. Too tall, too skinny. The result of poor breeding. Too tall, too skinny. I can think of no better anecdote to illustrate how far this has gone than our own experience stemming from our most recent breeding of our mares. Not far east of us on the Bergen Road and just north on the 766 there lived a man named Dale Rosenke, who bred splendid Clydesdales. One look at Dale’s sizeable herd was all it took to know that here was a man unscathed by the vagaries of modern horse-fashion. Here we saw a cornucopia of colour coupled with the best of what the old breed standard called for in the way of substance, with roans aplenty amongst the more solid bays and chestnuts, and with nary a black to be found. Dale said simply, “I breed primarily for quality.” We talked awhile of quality in horses, and in others things, the increasing lack thereof, and then he suggested he had a particular stallion we’d probably like to use. This stud went by the unpretentious nickname of “Wally,” and he was in my mind the best Clydesdale stallion I’d seen to date. Dark-brown with four whites and a modest blaze, he was not over-tall nor prohibitively big, (hugeness having its limitations as an asset in working horses as it does in all else in life) perhaps just shy of seventeen hands, yet he was beautifully built, with a short back and an abundance of powerful muscle, bone and “feather”, just the right amount of leg, and indeed, nothing that would conjure the term “coarse.” He moved wonderfully, with action and stride. A perfect old-school working Clydesdale. We had him on our place for a couple of months, and he also proved to be a gentleman, like his owner. (Perhaps too much so. He only impregnated one of our mares.)  A fine Clyde stallion of yore, Sir Everard, whose son earned $300,000 in stud fees. A fine Clyde stallion of yore, Sir Everard, whose son earned $300,000 in stud fees. Dale was by this time looking to downsize his herd somewhat. The downside of producing quality in draft horses these days being that you may have trouble finding folks who want it. Dale confessed, “Things are getting a little out of hand on the numbers front.” He offered to sell us Wally. If we had needed a stallion on the place, we’d have jumped at the opportunity, but we are not primarily breeders, needing a full-time stud with all that this entails. Wally ended up being auctioned, along with a few other stallions, taller and lankier and while still by no means of the inferior type to be found in some show rings, they were not to my mind of Wally’s calibre. These other stallions were Dale’s attempted concession to economics, he told me. (“I have to sell some horses,” he said.) These latter stallions brought multiples the price Wally did. Wally sold for meat prices, as I heard it. I only hope he didn’t sell for meat. A hundred years ago, I feel certain the reverse outcome would have occurred. The good news is, Wally’s genes are alive and well now amongst our little herd of registered Clydesdale horses, along with the genes of other fine examples of the breed, from Alberta to Ontario. We are eager to see how our latest youngsters turn out.  Emma and her new foal, Jenny. Emma and her new foal, Jenny. And with that in mind, it’s time to go do some training with “Bonnie,” one of our bay two-year-olds. It’s winter now, and a good time for this work. She’s smart, and training her is mostly a joy, as it mostly is with all of them. It would be encouraging to see a real renaissance in the working horse. I personally know of no younger men who are breeding Clydedale horses on any significant level. I hope they are out there. Donegal Clydes of Saskatchewan is dispersing their herd in 2014 and selling the farm to boot. Dale Rosenke has lamentably passed. Will their horses be scattered to the four winds? Will these random horses be bred as ours are, and if so, with any conscientious plan towards quality? Who will carry on the lineages of these magnificent beasts in a world focused instead on high-tech electronica, third rate subscription T.V., giant pickup trucks that are the Tonka Toys of the neotenic and other idiot claptrap? We are going to need them again, although most don’t understand this yet. It will be deeply challenging to us to admit that life is not the steady upwards trajectory of wonders this waning Golden Age has led us to fantasize it is, but rather a cycle of growth, maturity, decay and death that still applies as much to civilizations as to the lives that comprise them. That we need to make some paradigm shifts, that industrial technology has taken us firmly beyond the point of diminishing returns by this stage, to where it is doing us all real harm on a myriad of levels. We, my partner and I, are encouraged to be living right now in a an area where some of our neighbors have never entirely turned their back on the working horse – they still pursue significant aspects of their livelihoods, worthwhile livelihoods, from the saddle.  Jon goes haying with Raven and Gwyneth. Jon goes haying with Raven and Gwyneth. The horse remains to date the only sustainable power source available to us, on-farm and potentially off, that is even remotely practical. In the horse, if we care to resume where we left off, we will find great hope and inspiration, as we always did before this brief Age of Distractions. If we are wise, we will begin to gradually and strategically reincorporate the horse back into more areas of our daily lives as the era we have lived through continues to grind slowly down. If we are lucky, some of these horses will be Clydesdale horses. To behold these beasts is to glimpse magic, to spend a day working them, poetry, to count them amongst your friends… well, life gets no better than this.  Blue blood for him who races, Clean limbs for him who rides, But for me the giant graces, And the white and honest faces The power upon the traces Of the Clydes! -Anonymous

3 Comments

|

AuthorHave a look at our "Education/Contact" page for info on the author. Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed