|

0 Comments

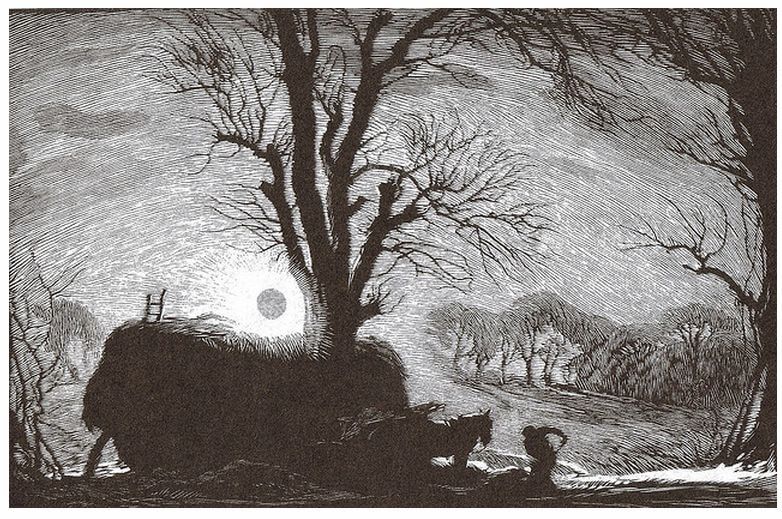

"One way or another, we all have to find what best fosters the flowering of our humanity in this contemporary life, and dedicate ourselves to that." - Joseph Campbell  C GEORGE SOPER. COPYRIGHT ON BEHALF OF THE AGBI, BY PERMISSION OF CHRIS BEETLES GALLERY, SPECIALISTS IN THE WORK OF GEORGE SOPER. WWW.CHRISBEETLES.COM All animals - the human one included - experience their phases of life. Birth, infancy, healthy growth, the relative stasis of maturity, decay, death. At some point during maturity, the zenith - the peak - is reached. That stage of life at which the system is functioning at the optimal level for producing the best of outcomes. Human beings have some control over how long this peak extends in our individual lives based on the decisions we make about how we live. Hopefully we make wise ones - avoiding falling into excesses of greed, gluttony, lust, acts of hubris, etc - and barring random Acts of God it's a long, rewarding ride. This is also true of civilizations, that they experience these phases of life. And if they are founded in durable concepts and run carefully with an overarching wisdom governing the outcomes of our indisputably enormous cleverness, with the right checks and balances and an eye to maintaining optimal scale, we can similarly extend that period during which the maximum benefit for the maximum number of citizens prevails. I wonder looking at the trajectory of the modern world, which let's say for argument's sake began in late 18th Century England with the birth of The Industrial Revolution, at which point between then and now did we enjoy our zenith? That point during which we were reaping the maximum benefits for the maximum number of people at the same time as enjoying a model that was arguably sustainable, that is, in overall harmony with its ecological context and therefore with the potential for enjoying the long-haul? What did life look like then? I picture this continent being at its zenith when it had the most hybrid vigor. That is, there were lawyers and businesspeople and doctors and firemen and architects and professional composers and musicians and academics, all the likely suspects of today in fact thriving in towns great and small with gorgeous structures built to last at the same time as there were mounted tribesmen chasing bison over epic swards while clans of the backwoods scions of rugged Ulster Scots up mountain coves made the air ring to the strains of Celtic folkmusic grafted to African rhythms and a mixed race of French/Indigenous lead a similar hybrid lifestyle on Red River of the North. Both ends of the human spectrum and everything in between. Specialists and generalists alike, with plenty of room both physical and economic for a multitude of approaches and economies. Underwritten in the settled places by mixed family farms practicing an enduring, human-scaled agriculture based on renewable power sources. Clean water and air for all and surrounded by a diversity in nature. The ultimate freedom of human expression in other words at the same times as allowing for a much greater freedom of natural expression than we currently see. The people who populate this vision are still amongst us. All the types are extant, but their ability to express their range of natures is sorely compromised. Given the awakening of the realization that we are at a juncture where the current model has become morbidly maladaptive, could we then begin work to re-create these conditions of true diversity? To use time honored yet ill-advisedly abandoned approaches alloyed with those modern advancements that show the most promise for affecting our longevity for re-introducing such hybrid vigor to our model? As a vaccine against our current steepening decline? Could we work to broaden the parameters while reducing the scale once again? To recover our cultural health, our vitality, reduce human conflict and conflict with nature? To enjoy the economic resiliency that such a model possesses? Choosing wisely this time, drawing from the vast breadth of all our experience and wisdom could we make it last for the sake of our children and other lifeforms? I don't know the answer to this. I don't think anyone does. But I know i am far from alone in asking these questions, in envisioning such an outcome. And I know it is worth attempting.  Lucy Kemp-Welch, art "The world needs less 'or' and more 'and'... " - Jim Dinning, former Alberta Provincial Treasurer Mr. Dinning, above quote, was speaking on the CBC Calgary morning show. He was talking about our approach to the future in a time of global climate crisis. Speaking of affecting the proper headspace for forging solutions. I couldn't agree with him more, although I doubt Mr. Dinning has in mind what I do as being included in that "and." I also wonder if he understands the full nature of our context, our circumstance today, being that our current mode of existence, our current model of civilization is incompatible with life on earth, including our own. He may, I don't know. I do believe many who didn't understand this even five years ago are understanding it now. Perhaps not verbalizing it quite yet, but feeling it, feeling it in their core. From the elders who have been around long enough to have developed a knack for synthesis of events into a larger whole to young adults and even youngsters only on the verge of adulthood become deeply skeptical of the narrow notion of "progress" that has been mainstream, it's a truth that is seeping into the collective subconscious. That our current civilization - global now - is in textbook decline and fall. I'm sure there'll be more on that to come, but in the meantime you may find this an interesting primer including as it does include the baseline reasons for the fall of civilizations: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/key-components-civilization/ Diversity is a key to resilience. A culture with a broad range of economic options is a resilient culture. We make much of diversity being a strength here in my country, Canada, in fact, but is my country truly diverse? I'd argue that it is not. We have one economy, for instance - a cash economy. And the bar is very high. To live in any comfort requires a LOT of cash, relative to the times of our ancestors. There is no more cheap land. There is a crisis of affordable housing. There is no real space left where the climate nurtures settlement in those proportionally insignificant fringes of this vast and mostly very nasty, barren second-coldest country on earth. Where anyone would want to live. (What proportion of Canadians for instance experience a definitive "Canadian winter" on an annual basis? Or have ever experienced one in full for that matter? Most of us living in extensions of moderate American climates?) There is an industrial economy dependent on the burning of endless oceans of hydrocarbons meeting our needs. There is a system of "just in time" delivery which like the rest of our system today, provides for next to no wiggle-room, as was painfully obvious for instance during the recent rail blockades. A system devoid of and with no room for patience with anything that stands in the way, regardless how legitimate. Most of us are urbanites now. Not much diversity here at the foundational level, anymore. We've winnowed away at diversity and at our options for diversity as we've grown and gelled into what we are today. How about being multicultural then, another thing Canada makes much of? We certainly give the outward appearance of being so in places like Toronto and Vancouver and increasingly elsewhere. But functionally? I don't believe it. I believe we have one culture here, a techno-industrial culture of material affluence focused primarily on growth in order to maximize profit, personal, household, national. Not satisfaction, not wellbeing, not right-livelihood, not mental health, not ecological health, not diversity - human or in the rest of nature - not human scale, not aesthetic living spaces, certainly not sustainability, not humane conditions for our livestock, not a future worth contemplating for our children, perhaps not even for ourselves depending how old - but rather maximum material profit. That is our culture. The people who come here agreeing to this. There are no nomads. No goat herders. No pastoralists, most places. No healthily functioning hunter-gatherers. With the exception proving the rule... Indeed I would argue that nothing could underscore the painful fact of our functional monoculturalism here in Canada better than our nascent foray into Reconciliation with our indigenous peoples. For the first time in the country's history we have gotten serious about extending some of the balance of power, some leverage to a culture within our borders who are significantly NOT on board with the way we do things, with the status quo of techno-industrial, developed-nation life. A very different culture. Our first serious stab at multiculturalism. And how has this been working for us? www.thestar.com/politics/federal/2020/02/11/reconciliation-is-dead-and-we-will-shut-down-canada-wetsuweten-supporters-say.html www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-reconciliation-isnt-dead-it-never-truly-existed/ Not much wiggle-room there either it seems, even at what is really just the bi-cultural level if we're honest. This is just with two competing cultures flexing their powers. What if we were to throw a few more opposing cultures into the fray? Yikes! In reality, it seems to me while through the homogenizing forces of monoculturalism as brought on by techno-industrialism and globalization we are as a country, and a globe no less, rapidly laying waste to what little is left of the former diversity of human and other lifeways, we are at the same time a civilization of profoundly byzantine complexity affording us little flexibility to rectify our problems. The mechanisms governing our global economy being so complex that the parameters surrounding their healthy functioning are no longer adequately comprehended by anyone, making for a very tenuous grip on things. Another fundamental cause implicated in the collapse of civilizations, in fact. Each new layer of complexity leading to an ever heightened vulnerability in the system such that the whole thing eventually comes down for the impossibility of even fathoming all the balls in play, their trajectories, let alone keeping them in the air. One tiny screwball - say for instance a stab at true multiculturalism in a system with room alone for total consensus to function - and the cascade of disruptions this engenders, each one of which we must attempt to separately address, may prove fatal to the system or compound a series of events fatal to the system. And yet what are we calling for to address our deepest woes today? Colossal windfarms. Electric cars. Vast arrays of solar panels. Artificial intelligence. Trips to Mars, even! All the attendant layers. More and more and more complexity. Ever heightened vulnerability. And this is just pertaining to our economies. Nevermind trying to come to grips with our effects on the parameters governing the functioning of ecosystems, which can never be fully known. "The ability to exert control on economies depends on having sufficient control of the system parameters..." - Michael Harre et al, University of Sydney, Australia I personally doubt we can avoid the collapse of our current mode of existence, our global civilization. For one thing, all classic signs suggest we are very firmly in its throes already. Are we surprised? Having long acknowledged our model being unsustainable? We shouldn't be. Where we are now, as the inevitable outcome given the basic flaws of the model we have been subscribing to since probably the beginning of the industrial revolution, being the difference between having a problem - something that can be solved - and being in a predicament, which can only be negotiated. Successfully or not. You are in a canoe. You hear the rapids ahead - a problem. The solution being to paddle to shore. Fail to do this and you find yourself in the rapids - a predicament. There is no solution to being in the rapids once you are in them. Your only hope is to have in place the systems skills beforehand to come out the other end. Or barring that, to be able to make necessary adjustments on-the-fly in time to avoid being swamped. So lets get the skills in place, I say! We cannot know where the ultimate tipping points lie, the thresholds beyond which negotiating our predicament will become much more difficult. Let's acknowledge where the present model is headed without focusing on the inevitability of where this is all going, but rather focusing on the possibilities for engineering what awaits us on the other side. On the freedom we will have to do better with a clearing of the slate. Starting in the present. Let's aim to increase our functional diversity for a change. Towards more "and" in the system. "An emphasis on a point of no return is not particularly helpful for bringing about the conservation action we need. We must continue to seek to reduce our impacts on the global ecology without undue attention on trying to avoid arbitrary thresholds." - Professor Barry Brook, Director of Climate Science, University of Adelaide *Part Two next week... In the fall of 2019 fresh from a screening of the film “Unbranded” (https://youtu.be/swX4BLbmBNU) documenting four friends riding mustang horses from the Mexican to the Canadian border, with an assertion by the leader of the expedition that the ride could not have been completed on domestic horses fresh in my mind, I rode our Clydesdale mare Jenny in the Bearberry horse rally in our hills. The event was 100 riders strong with the proceeds of the registration fee going to charity. Arriving fairly early to the staging grounds, there was a fair bit of lounging about that went on before the ride. It was in chatting to one gentleman about the pros and cons of this and that breed for this and that purpose that I became informed of the Wild Horses of Alberta Society – or WHOAS – that had their headquarters not far south from where the ride was taking place, and that they had several wild horses available for adoption. Now here is something I went away thinking.

I visited the webpage of WHOAS. (Check it out if you wish - https://wildhorsesofalberta.com/.) There was one horse up for adoption at the time. He was a young gelding, not quite three judging from his teeth, liver chesnut in colour and the name they had given him was “Eli.” He has an excellent disposition, and has proven to be friendly and willing his description went. The two photos suggested a well-proportioned animal aside from the head, which looked rather long for rest of the critter, relative even to the reason we coined the term, “horse-faced.” I decided to go check him out in person. Here was the real deal, after-all, just beyond our doorstep and ready for a new home. I should mention that I have long been fascinated with tales of tough breeds of horse forged in the crucible of harsh lands. Breeds like the Morgan horse, the Canadian. The Newfoundland dog. Which isn't a horse, but rather a dog. But you know what i mean, right? I fancied that if I were to one day keep a horse explicitly for riding, as opposed to our big Clydesdales that have been doing double-duty as riding horses, I would seek out one of these breeds. The caveat here being that these breeds have been around for many, many horse generations at this point, and are umpteen generations removed by pretty cushy times from the forces that resulted in their outstanding breed qualities. It only makes sense that these qualities will have endured a certain dilution of their seminal potency. Yet in the great expanse of hills on the eastern fringe of which is located our farm roam the largest bands of wild horses, or mustangs, in Alberta. Horses that are 0% removed from unforgiving evolutionary pressures. (There is debate over whether they are more properly termed “feral,” but everyone around here calls them “wild,” “wildies” or “mustangs” and that works for us.) I had known for years that periodic trapping initiatives occurred in order to cull these bands, which are not popular with some ranchers for the fact that they eat grass they’d prefer went towards fattening some horde of squat beeves. Wouldn’t it be something to get your hands on one of those for riding I’d been reflecting of late. What could be better as a mount for these hills than a horse forged in these hills? But i wasn't sure how that might be practically effected. Until now. First impressions of Eli were very good. The length of his head was in reality perfectly proportionate, forced perspective being to blame in the photos. I spent some time with Bob Henderson, who formed the society in 2001. ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=azKFiMyerr8) The society seemed to think our farm was a good match for Eli, and we agreed to adopt him. This was in October. Born and bred in the hills to mustang parents, Eli had been running wild until August, when as sometimes happens with bachelor males, he entered the pasture of a remote farm to woo the domestic mares there, in company with some of his adolescent friends. WHOAS was called to come and remove the horses, as this is one of the functions of the society, to help keep these animals out of trouble. The horses were trapped in a corral and trailered to their facility where basic preliminary gentling was accomplished by a handful of experienced volunteers. Eli had learned to stand in a stall tied and to lead on a rope in a halter. He was suspicious of me at first, and I spent some weeks going to visit him daily at the facility before trucking him home well into November. He was kept in the corral with access to the big barn where I kept up the routine of tying him and graining him with oats daily to help him settle in and become used to me. He got to meet our Clydesdales through the slats of his corral fence, further separated by a solar-powered hot strand (electric wire) spaced to keep the horses off the fence but almost able to touch noses. The big Clydesdales spent a lot of time at that fence. A month later they were introduced in the central paddock and all has gone as expected there, that is to say, plenty of jostling to establish herd hierarchy with no injuries. The little mustang looks half the size of the big horses, which he pretty much is, but he holds his own, even managing to mount the big girls when they are receptive. He’s gelded mind-you, and it’s a waste of time for the girls beyond being pleasant society, I guess. Like dancing with the castrati. Training Eli has been a joy. In very short order he “joined up” with me, following me about like a dog and calling to me when I first left the house. Contrary to what you might expect from a horse with wild genes in him that go back to explorer David Thompson’s era (1800), this horse has proven more sensible and less excitable in training than even some of our Clydesdales, a breed legitimately famous for its calm nature. It’s as though natural selection, in addition to weeding out all the physical liabilities in these horses, has weeded out the mental ones, too. And this of course makes perfect sense. In a natural environment that includes puma, grizzlies, and big packs of the world’s largest wolves, or even just random grouse exploding into flight from underfoot, an overly flappable horse would not last. Too much energy would be wasted. Mistakes would be made, potentially fatal ones. Condition would suffer, and winter would come. Injuries might happen and there would be the wolves. And so they have become like the zebra in relation to the lion. They know when it’s time to worry, and just as importantly, when it’s not, and they process the distinction efficiently. I’ve measured my new boy for a new saddle, a nice one that will fit me, too. This comes in March. He has learned so fast that I could easily have been riding him by now in the training saddle, but I am in no hurry. Wait til the snow and ice are gone and the footing is better for that. In the meantime, it took him about a day to learn to respond to bit pressure, to get used to the pressure of my foot in either stirrup, and he now takes my full weight flopped over the saddle like a halibut calmly enough to be sniffing around for something to nibble whilst I am up there. I’m very much looking forward to this coming season. It's February end and Eli is losing his winter coat. I’ll keep you posted. Thanks for reading! - Jon Shelter, water, energy, food. The challenge we face today lies in rediscovering fundamental systems that are not fundamentally deadly. In the 1970’s, there began a movement that lead to the development of the various “Organic” certification and labelling systems and bodies. These systems have been a measured boon to food quality, and therefore to human beings, the land - to the entire biosphere - the world over. Having taken us this far, we at Thompson Small Farm believe that there is still further to go. We believe it is time we reinvented the term “Organic” and the systems and governing bodies that lie behind the term. To help us illustrate to you why we believe this, we’d like you to take at look at these two pictures, each depicting a modern, working farm engaged in wheat-harvest, and tell us which picture, at first glance, you think best represents a system we might label “Organic”. I expect that by basic instinct, most people would choose the picture on the left, the first picture, as being a better representation of an organic farming system. Paradoxically, the first picture is of a working Amish farm that has no Organic certification, while the second picture is of a farm with Organic certification.

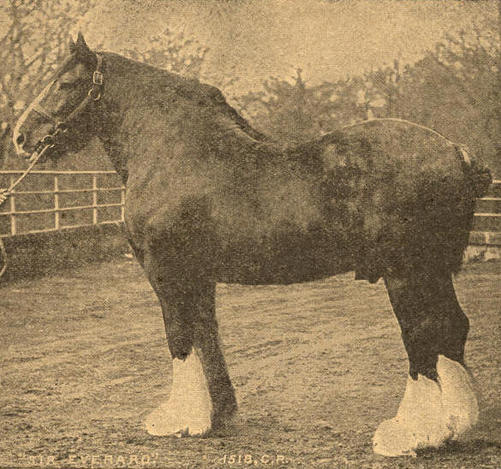

If you are thinking "there is something wrong with this picture," well so are we. You already understand, instinctively, without having to give the situation any subsequent thought, why the term "Organic" needs redefining, why the Organic systems of certification need revamping. But let's do give it some further thought. Why do our instincts tell us one thing, but Organic labeling tells us another? The reason is that while both pictures represent a fundamental system - food production - one depicts a system that is fundamentally sustainable, the other a system that is fundamentally deadly. One depicts a way of life that has the potential to sever our ties to processes like the tar sands, the other requires that we mine the tar sands for all they're worth, and then find some more tar sands to mine, and oil shale to frack, and etcetera on into perpetuity. One picture depicts a system that is embedded with its own limits of scale commensurate with the healthy requirements of a living planet, the other depicts a system which knows no limits of scale. One depicts a system that sustains communities and family enterprise, the other a system that symbolises the ruin of the family farm, rural communities and the corporatization of our lives. One depicts a system that has the power to combat climate change, the other the very system that created the problem. One depicts a scene that is all about local scale, the other a scene that has no choice but to be globally scaled. We could go on. We do think it is a good thing that the farm depicted on the right must fulfill the requirement of using no agricultural poisons in the production of our food. A very good thing. We are by no means condoning abandoning the strides towards food purity the Organic movement has made, nor the principles that guide us to produce the purest quality food. On the other hand, keep in mind that when you are looking at a tractor - any tractor, (it needn't be a behemoth like this one) just like when you are looking at a horse, you are looking at all the things that go into making that object possible. When you look at a tractor you are looking at tar sands, oil shale, the removal of entire mountaintops in places like West Virginia and British Columbia, the poisoning of watersheds, the wage enslavement of once autonomous people in factories and mines, the compaction of the soil, emissions, smog, climate change, a culture of conquest and war, cultural genocide, the list goes on. How "organic" does this seem to you? How "clean", in reality, is the food a farm like the one in the second picture produces? We would argue that the poisoning goes on, it's just been outsourced away from your person. Temporarily. The problem being, it is still making its way back to you, in myriad ways. How about the horse as a fundamental power source on the farm? In the case of the horse you are looking at a power source that necessitates a human scale of enterprise. You are looking at a power source that reproduces itself, that gets all it needs from the farm, from the produce of the sun - the horse eats what you can grow as fuel, and doesn't require a massive industrial process to convert that fuel into work, nor to be there available to you in the first place. You are looking at a power source that produces emissions that are actually useful to the land: they give back to the land what is taken out as fertilizer. You are looking at a power source that is fundamental to pasture management systems that build, rather than degrade, topsoil and create a carbon sink that helps combat climate change. You are looking at a system that does not require any of the deadly processes listed in the case of the tractor in order to exist and function. You are looking at a power source that does not compact the soil. You are in fact, looking at the only solar powered tractor known to man. And while it is true that much of the equipment that is used in horse-farming today is derived from industrial processes, it is also true that the level of scale to produce such equipment can also come from the farm itself, re-utilizing materials such as steel that are currently available in vast abundance without further degradation of the biosphere. And that's the bottom line, why one picture just "feels organic" and the other does not. One picture is a picture of sustainability, and the other is a picture of a terminal condition. Only one of these pictures depicts a way of life that has a future. The picture on the left, then, depicts something that is organic, while the picture on the right depicts something that is, in reality - regardless of how we label it - not. And that's what we'd like to see taken into account where any Organic and other similar labelling systems come into play. Sustainability. For if a farm is not sustainable, if it is failing to work towards severing ties with all the fundamentally deadly processes we've provided a brief list of, how can it possibly be considered "Organic"? Rediscovering systems that are truly organic, that are sustainable, is not going to happen as an event. It is going to continue to happen as a process. It is going to happen as a transitioning that is initiated on a proactive farm-by-farm basis, at a pace that is ideally comfortable for the farmers involved and works with their economics rather than against them. It is going to happen as a process that is driven by a people, a customer base, demanding that sustainability be the issue that is brought to the fore in food production. All the while keeping in mind that change, any change - even positive change - requires us to step outside our comfort zones and develop new ones. The pioneers of the Organic Movement were part of this change, part of this process. Let's not drop the ball now. Let's keep producing quality food while adding incentives to farmers who can demonstrate they are taking steps to make their farms one day truly sustainable. "Organic" in a holistic, rather than just a specific, sense. Revamping food certification systems is one way we could offer incentive to farmers to do so, and would provide further assurance of quality - Big Picture Quality - to customers. Focusing not just on food purity, but on the even more important issue of sustainability.  Andrea and I didn’t have thirteen children, but we did have something small, hairy, and unexpected arrive this December. Mable is our sole remaining milk cow. This is after selling her mother, Mary. It seems like a terrible thing, to sell someone’s mother, but Mable doesn’t seem to care. Her mother was a full-blood Jersey, a breed prone to milk-fever, so we crossed her to a Milking Shorthorn sire, a breed not known for milk-fever. This made sense, to us. Mable has the red-and-white colouration of the dad, overlaid with a nice brindling. Now, here’s the thing about yaks: you can cross a yak with a cow, but the resulting bulls are sterile. The cows remain fertile. Prevailing wisdom surrounding yaks says that if you wish to accomplish such a breeding, you must separate the yak bull together with the cow you wish to breed. He is something of an elitist, you see, and will only breed a cow when the pickings get – or are rendered – slim. Mable was not separated from our small yak herd and we didn’t worry. We thought one day we might separate her with Clint, our yak bull, when the time seemed right. Anyway, she started bagging-up in early December, but not much, so we didn’t think much of it. “She’s becoming a woman,” that sort of thing. Nothing else to cause alarm seemed to be occurring. It got cold, so we put her in the old milking barn, the one built by Arnie Arnesson way back when and that we put a new metal roof on because it was on its last legs, although it should stand now for a long time. Log barns, so the prevailing wisdom goes, don’t fall over, they just get more squat over time, like the folks that build them; and all the other folks, too. We hope the prevailing wisdom surrounding log barns has more substance behind it than the prevailing wisdom surrounding yaks. You see, it had only been a few days that Mable was snug in her barn when I went in and thought, “Who let that mongrel in here with the cow?" But I was wrong. Mable had given birth. A little calf was there, small, hairy, red-and-white like the mom, and already frolicking about, his name: Herman Nelson. Half-yak, one-quarter Jersey, one-quarter Milking Shorthorn. Not only did we have a new calf, we had learned something more about Clint, our yak bull, Herman’s dad. Something that we hadn’t thought about before, something that would not have occurred to us: he was not much of a reader. And this is the thing about yaks, the other thing. Their calves are small, like a sewing machine. They make no more difference to the mother’s girlish shape than a couple of beers make to the shape of a long-haul trucker. The result being that they tend to simply appear, if you are not watching closely. If you do watch closely, they appear anyway. Just like our ancestors did. The Suffolk Punch will keep the road, The Percheron goes gay; The Shire will lean against his load All through the longest day; But where the plough-land meets the heather And the earth from sky divides, Through the misty Northern weather Stepping two and two together, All fire and feather, Come the Clydes! - Will Ogilvie  Gwyneth, one of our registered mares, at pasture. Gwyneth, one of our registered mares, at pasture. I am blessed in recent years to be sharing my life with the most magnificent of the heavy horses, indeed with one of the most splendid creatures ever to grace this earth: the Clydesdale horse. More, I have had the double blessing to share many a working day with them – training, ploughing, discing, harrowing, haying, hauling, and sometimes, doing my bit to teach others to do the same. The Clydesdale horse originated in the Clyde River valley of Scotland, at least in ancestral form. The Clydesdale of the modern era is a mixed bag, however, the most so of all the heavy horse breeds. Herein lies its versatility, say some. While there are more powerful horses for working the furrow alone, or for taking to pulling contests, none is better for more jobs than the Clyde. Their breed standard calls for the ideal of substance without coarseness; neither grossness nor bulk, but rather quality and weight. An apt description, a person is led to think, while one is there in front of you.  Seeding Canadian peas with four abreast of our Thompson Small Farm Clydesdales. Seeding Canadian peas with four abreast of our Thompson Small Farm Clydesdales. If you ever were to hitch a Clydesdale with a Percheron or Belgian and make off down the road, you might note that the others take almost two strides for every one of the Clyde. This is a function of build. The Clyde has the long cannon bones and high rump of a nomad, albeit a very powerful one, the other two are “shorter coupled,’ having shorter bones combined with a hugeness of mass that can indeed be aptly described as coarse by comparison. This makes the other two very powerful, but comparatively slow. I well remember three days I spent mowing hay with Skeeter Thurston, an ex-pat Nebraskan, on his ranch north of Elmira. He was one of the rare ones, and I’ve known a few of them here in Alberta, who believed us foolish to entirely turn our backs on the old, millennia proven ways, and lived their beliefs. We hitched our teams to McCormick-Deering Number Nine machines, the Cadillac of the old horse-drawn mowers, these ones with six foot sickle bars; he with his team of American Belgians and me with a team of our Clydes. He instructed me to lead off, and away we went around that relentlessly hilly quarter under the late August sun, traces jingling and knives whirring, but never making such a racket that the call of the Meadowlark was lost to us, nor so obtrusive as to scare away the sentinel hawks bent on the mice we would stir. By the time we’d made a circuit, my Clydesdales and I were no longer in front of Skeeter, we were coming up behind him. Skeeter suggested that my horses were in better shape than his that summer, but it is also true that it is this quality of covering ground that prompted one old Clyde breeder of Saskatchewan whom I got to know a little while making use one of his stallions to quip in good-humored rivalry, “Sure the Belgian can haul a little more of a load. Me, I prefer to use a Clyde and actually get the job done!” It is this same quality of a long, smooth stride that made them ideal for road and town work, and today, for riding.  "Bay-with-four-whites" Clydesdale. An excellent example of the breed. "Bay-with-four-whites" Clydesdale. An excellent example of the breed. It is said that the demise of the horse era heralded a new age in which horses were, on average, treated much better. I suppose this is true, for those horses that weren’t turned into dog-food, and there were literally millions of them that met this fate. (Although I suppose, really, it was not so much the dog but the tractor that ate them.) In more recent decades, the heavy horse has made a minor comeback, although I fear that forces may again be turning against them. In fact, although the Clydesdale horse is probably the best known of the heavy horse breeds on this continent today, thanks in large part to the advertisements of the Budweiser beer company, it is ironically also one of the rarer ones, and is under watch by various Rare Breeds societies. Aside from a precipitous drop in numbers early in the 20th Century, the end of the horse era created some other issues for the Clydesdale. When they were being bred for the farm, the colour of the horse took a back seat to quality. The Clydesdale evolved as a colourful, even flashy horse. The best ones tend heavily towards roaning, which in this breed is actually more of a bold marbling and splotching, than it is the subtler overall wash of flecking called “roan” in other breeds. Against a background of just about any colour a Clydesdale horse can be overlaid in a liberal splashing of white, with the white predominating in extreme cases. It is these roan horses that carry the quality genes in this breed. One second-generation Clydesdale breeder of renown assured me that if you take the top ten Clydesdales at any show where true quality is the concern, eight of them will be roans or have a strong lineage of roaning. Yet today with the Clydesdale, we see a trend towards uniformity – solid bay with four white feet, or “four whites,” as seen in the Budweiser hitches. While there are many fine bay Clydesdales (left), quality will suffer if this is what you are breeding for alone in this horse. Worse for the breed has been the fashion towards black Clydesdales (with the signature four whites and facial blazes, of course.) One colour that is rare in a Clydesdale is black, and it is hard to breed one of real quality.  Sarah, a "blue-roan" daughter of Emma, in wolf-willows. Sarah, a "blue-roan" daughter of Emma, in wolf-willows. But worst of all for the quality of this breed has been the modern trend that is affecting all heavy breeds to produce an excessively tall, lanky animal with less muscle – again, an animal of poor quality. While the Clydesdale is leggy for a heavy-horse, it is meant to be subtly so. But now we see a case of fashion over function predominating in many show rings. Some very strange looking ‘work’ horses have been the result, and it is no exaggeration to say that some of them are tending more towards huge, mutant track horses than otherwise. I see this as a trend driven by distinctly urban sensibilities, rather than rural ones that were the genesis behind these breeds. We’ve seen this with many dog breeds as well, the impetus being towards producing attractive nitwits. The trend mirrors our own human trajectory with the sweeping move away from the land we’ve experienced in recent decades. The less useful we become ourselves and to ourselves, the less useful we expect our animals to be. The danger here being that when the day returns that demands a general competence of us, we will have lost all ability to meet these demands. And so will have our animals.  The result of poor breeding. Too tall, too skinny. The result of poor breeding. Too tall, too skinny. I can think of no better anecdote to illustrate how far this has gone than our own experience stemming from our most recent breeding of our mares. Not far east of us on the Bergen Road and just north on the 766 there lived a man named Dale Rosenke, who bred splendid Clydesdales. One look at Dale’s sizeable herd was all it took to know that here was a man unscathed by the vagaries of modern horse-fashion. Here we saw a cornucopia of colour coupled with the best of what the old breed standard called for in the way of substance, with roans aplenty amongst the more solid bays and chestnuts, and with nary a black to be found. Dale said simply, “I breed primarily for quality.” We talked awhile of quality in horses, and in others things, the increasing lack thereof, and then he suggested he had a particular stallion we’d probably like to use. This stud went by the unpretentious nickname of “Wally,” and he was in my mind the best Clydesdale stallion I’d seen to date. Dark-brown with four whites and a modest blaze, he was not over-tall nor prohibitively big, (hugeness having its limitations as an asset in working horses as it does in all else in life) perhaps just shy of seventeen hands, yet he was beautifully built, with a short back and an abundance of powerful muscle, bone and “feather”, just the right amount of leg, and indeed, nothing that would conjure the term “coarse.” He moved wonderfully, with action and stride. A perfect old-school working Clydesdale. We had him on our place for a couple of months, and he also proved to be a gentleman, like his owner. (Perhaps too much so. He only impregnated one of our mares.)  A fine Clyde stallion of yore, Sir Everard, whose son earned $300,000 in stud fees. A fine Clyde stallion of yore, Sir Everard, whose son earned $300,000 in stud fees. Dale was by this time looking to downsize his herd somewhat. The downside of producing quality in draft horses these days being that you may have trouble finding folks who want it. Dale confessed, “Things are getting a little out of hand on the numbers front.” He offered to sell us Wally. If we had needed a stallion on the place, we’d have jumped at the opportunity, but we are not primarily breeders, needing a full-time stud with all that this entails. Wally ended up being auctioned, along with a few other stallions, taller and lankier and while still by no means of the inferior type to be found in some show rings, they were not to my mind of Wally’s calibre. These other stallions were Dale’s attempted concession to economics, he told me. (“I have to sell some horses,” he said.) These latter stallions brought multiples the price Wally did. Wally sold for meat prices, as I heard it. I only hope he didn’t sell for meat. A hundred years ago, I feel certain the reverse outcome would have occurred. The good news is, Wally’s genes are alive and well now amongst our little herd of registered Clydesdale horses, along with the genes of other fine examples of the breed, from Alberta to Ontario. We are eager to see how our latest youngsters turn out.  Emma and her new foal, Jenny. Emma and her new foal, Jenny. And with that in mind, it’s time to go do some training with “Bonnie,” one of our bay two-year-olds. It’s winter now, and a good time for this work. She’s smart, and training her is mostly a joy, as it mostly is with all of them. It would be encouraging to see a real renaissance in the working horse. I personally know of no younger men who are breeding Clydedale horses on any significant level. I hope they are out there. Donegal Clydes of Saskatchewan is dispersing their herd in 2014 and selling the farm to boot. Dale Rosenke has lamentably passed. Will their horses be scattered to the four winds? Will these random horses be bred as ours are, and if so, with any conscientious plan towards quality? Who will carry on the lineages of these magnificent beasts in a world focused instead on high-tech electronica, third rate subscription T.V., giant pickup trucks that are the Tonka Toys of the neotenic and other idiot claptrap? We are going to need them again, although most don’t understand this yet. It will be deeply challenging to us to admit that life is not the steady upwards trajectory of wonders this waning Golden Age has led us to fantasize it is, but rather a cycle of growth, maturity, decay and death that still applies as much to civilizations as to the lives that comprise them. That we need to make some paradigm shifts, that industrial technology has taken us firmly beyond the point of diminishing returns by this stage, to where it is doing us all real harm on a myriad of levels. We, my partner and I, are encouraged to be living right now in a an area where some of our neighbors have never entirely turned their back on the working horse – they still pursue significant aspects of their livelihoods, worthwhile livelihoods, from the saddle.  Jon goes haying with Raven and Gwyneth. Jon goes haying with Raven and Gwyneth. The horse remains to date the only sustainable power source available to us, on-farm and potentially off, that is even remotely practical. In the horse, if we care to resume where we left off, we will find great hope and inspiration, as we always did before this brief Age of Distractions. If we are wise, we will begin to gradually and strategically reincorporate the horse back into more areas of our daily lives as the era we have lived through continues to grind slowly down. If we are lucky, some of these horses will be Clydesdale horses. To behold these beasts is to glimpse magic, to spend a day working them, poetry, to count them amongst your friends… well, life gets no better than this.  Blue blood for him who races, Clean limbs for him who rides, But for me the giant graces, And the white and honest faces The power upon the traces Of the Clydes! -Anonymous  They only look relaxed. Those meat chickens couldn't be safer. Caroline Leppert photo. They only look relaxed. Those meat chickens couldn't be safer. Caroline Leppert photo. Andrea is working in the farmyard, close to the gate that opens out to pasture. Some of the big grazers are coming down the corridor to the central paddock for water. There, approaching amongst them, she becomes aware of something small and incongruous. It is the fox that has been plaguing us, beautiful and relentless little killer. It is there using the large animals as a screen to approach the field-chickens unnoticed, or so it hopes. But it doesn't work. Just as she's about to shout at the interloper, a streak of wolf-large whooly fur rockets out from behind her, followed by another and yet another These are our protectors, our livestock guardian dogs. They are almost on the fox before it realizes the very real peril it is in and bolts. By now our two other farm dogs have joined the chase. The fox won't be getting a free lunch from us, not today. Still, it is very lucky not to have been shredded.  Sounder (that white thing) guards the field chickens free ranging from the eggmobile. Sounder (that white thing) guards the field chickens free ranging from the eggmobile. The working group "livestock guardian dogs" is composed of a number of breeds, including but not limited to: Great Pyrenees; Maremma; Akbash; Komondor; Ovcharka. The origin of these dogs is lost in antiquity, but it seems they share a common ancestor that originated perhaps in Asia. They are designed for a pastoral style of livestock husbandry, that is, one that relies on free ranging stock out on open pasture. They are raised from pups right alongside those animals they are meant to guard, and long instinct borne out of careful selection over millennia instructs them that their job is to watch over this "family" and all it contains, and to guard it with their life. (In our case, we raised our pups alongside our chickens. The yaks and the draft horses don't need protecting.) They tend to be large dogs, capable of standing a chance against a wolf or bear if necessary. Custom sometimes suggests the dogs should receive a minimum of human contact in order for them to bond with their animal charges, but this hardly seems to be the case, Ours are extremely bonded to us yet do an exemplary job guarding, and at only slightly over a year old, they will only get better - it takes these dogs up to three years to fully mature. At any rate, we cannot imagine the loss that would be ours should we not have their friendship as we do - they are delightful creatures, full of character and personality. Furthermore, any dog this large, and programmed for savagery as the situation requires, certainly needs socialization with humans. Unless you are Ghenghis Khan, an individual infamous for harnessing his anger to produce a desired outcome. Then again, while some people who come on your place will certainly deserve to be bit on the ass by a large carnivore, Mr. Khan did not live in such a litigious age as we do today.  Call a Komondor's bluff and you'll find out it's not bluffing. Call a Komondor's bluff and you'll find out it's not bluffing. Amongst the breeds that compose this group of dogs are those famous for wandering large distances. I once had a friend who raised Pyrenees on his farm, for instance, this being one of the roaming breeds. When I drove over the prairie to visit him in winter, it was not uncommon to begin encountering the tracks of his dogs in the snow many miles out on the plains before I reached his farm. Two of his pups were our first livestock dogs, in fact. We couldn't keep them on the place, nor to be honest, anywhere near it. I suppose we got them a little old to bond properly with the stock. Whatever the case, and while I personally found their free-spiritedness both fascinating and endearing, the dogs were effectively useless to us when they were five miles away and the coyote five feet from the fence. We reluctantly returned them.  Ranger. Ranger. Our livestock dogs that are on the place now - the brothers Sounder, Ranger and Hunter - are a trio we rescued as young pups. Their mother is a Komondor, a huge and intriguing breed that is more aggressive yet less prone to wander, their dad one of my friend's old Pyrenees. Since spring has come on and the chickens are out ranging well afield, these new dogs have become pretty much the homebodies, tied to their job. But there was a time last winter when i was off deer hunting in the big woods that abuts our place, several miles deep into the sylvan fastness, and came upon tracks on a steep and trackless slope that i first took to be those of a pair of very large mountain lions. Wolf-sized prints. (There are lions here that leave such large tracks.) Then I detected claw-marks, which the lion of course, having retractable ones, does not leave. The prints were too round and catlike, however, to be those of wolves, found here as well. Then it suddenly dawned on me why these prints were looking so familiar as I continued to examine them. They were the tracks of my own pack! I was happy knowing they were out engaging the wilds as I was. Our dogs are interesting to us on many levels, not the least of which includes how their physical appearance lends insights into the ancient ties between the livestock guardian breeds. For while both their parents were entirely white, two of the brothers are predominantly grey. A person might well wonder why this is so, yet in learning more about this guild of canines, will discover that other guardian breeds known from geographic regions abutting those from whence the "Komondorok" (plural for Komondor) and Pyrenees sprang indeed commonly have markings, hues and patterns not unlike those of our crosses. Breeds like the Pyrenean Mastiff, and the South Russian Ovcharka. The long buried lineages emerging readily from the ether of long ago with a little genetic coaxing.  Hunter sleeps (lightly?) where he's needed: up against a henhouse. Hunter sleeps (lightly?) where he's needed: up against a henhouse. It is normal these days when new laws are passed out in the country for them to represent some level of inhibiting nuisance to those rural folk living traditional rural lives. So it was with relief and hope that we reviewed new ordinances in our home county of Mountainview. In Mountainview County, it is now writ in law that a barking livestock protection dog is not to be considered grounds for nuisance complaints. Nor is a livestock protection dog that is roaming off-property in the pursuit of its duties to be considered a "dog-at-large." Rather, these dogs are now being protected as the vitally contributing rural citizens that they are, essential elements of a productive rural fabric. Now that's the kind of "progress" we need to see more of. Laws that actually favor, rather than hamstring, traditional farm economies.  Meat bird pens with eggmobile in the background, on Thompson Small Farm. Meat bird pens with eggmobile in the background, on Thompson Small Farm. All Flesh is Grass, says the Book of Isaiah, and so on our farm, that's where it begins - with the grass. The production of our free-range eggs and meat chickens is a good example of the genesis of this adage. To produce the best chicken and eggs possible, we must raise the birds on pasture, and so rather than focusing primarily on the chickens, we must practice farm management principles that are best for the health of this pasture first. Grass is designed with grazers in mind. Grazers in nature run in tight herds and move around a lot. They stay tight as defense against predators, and they move around so that the grass beneath their feet is always fresh. Any given blade of grass is nipped off once and left alone as the grazer moves on. The root of the grass dies back according to the amount grazed off above the surface, and the dead root elements decompose into topsoil. The blade of the grass then has a growth surge in response to being nipped, and the roots do too. Nip it more than once in too short a span of time, however, and you stunt the blade and the root, both. Hence the old adage, "Keep down the shoot, kill the root." The first step then in raising the best chicken and eggs, is to have a herd of large grazers to keep the pasture healthy and prepare it for the chickens. On our farm, this herd is composed of draft horses, yaks and dairy cows. In order to mimic the patterns of natural grazing just described, we move them daily to fresh pasture, enclosed tightly in a temporary paddock delineated by solar-powered electric wire and just large enough to completely graze in one day, no larger. They're on there, they hit it hard, and they're gone, leaving the grass alone to respond naturally. They aren't brought back to the same spot until the grass is ready. Your grass tells you when and where to graze the animals, in other words. This system is called "mob grazing." It is not only a key to healthy pasture, it is a potent tool in combating climate-change, for while over-grazed pastures which are the norm today lead to desertification and absorb little carbon-dioxide, and ungrazed pastures emit carbon dioxide from their thick decomposing thatch of dead, unused grass, mob-grazed pastures maintain optimum growth and absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide. This method on its own, done correctly and with attention to detail, would result in very good pasture at about four times the volume a conventionally grazed pasture provides, but now we incorporate the chickens to add diversity to the system, for resilience is contingent on diversity. Our meat and egg birds are rotated onto the paddocks the big grazers have prepared as the grass is coming back, for the chickens don't like the grass too long. The meat birds are kept in large, movable pens to protect them from predators and the elements, and the more agile egg birds range out from fixed-coops and a mobile "eggmobile," protected by big, shaggy dogs whose working lineages are lost in antiquity. They nibble the grass without having the impact of the herd animals, and they eat the insects and take in all the nutritional elements of a healthy sward. They add their droppings to the grounds, an incredible injection of soil health-inducing nitrogen that the grass would not be able to incorporate were it not for the fact that it were being mob-grazed and kept in a hyper-productive state. The chickens in turn take in many healthy antibodies and of course receive plenty of ultra-violet from the sun. This way, we circumvent the need in today's large and vulnerable meat birds for the constant infusions of antibiotics required to keep them alive in the crowded, stressed battery barns they were genetically designed for, and where the chicken you're used to eating comes from. And the eggs you get our way have been shown to be six times more nutritious than conventionally raised. And so as a by-product of keeping our pasture in the best shape it can possibly be in, we get the finest chicken and eggs possible. We also build topsoil, maintain healthy herds, feed draft-animals that provide us with the sustainable power that machines cannot, at the same time as combating climate change. It's a most elegant system. Enjoy your chicken!  Yaks and horses enjoy the first day of the end of the Hungry Gap. The most efficient way to graze a pasture is with a mixed-herd. There are cows and chickens in this mix, too. Yaks and horses enjoy the first day of the end of the Hungry Gap. The most efficient way to graze a pasture is with a mixed-herd. There are cows and chickens in this mix, too. III III In traditional farming, there comes a time of year in the early spring when one must lock their animals away in a paddock. This happens when the grass begins to green-up, and the purpose in doing this is to let the pasture get a good start before beginning the season's rotation of the grazers. The paddock they are kept in for this period, usually lasting a month and a half or two, is called a "sacrifice area," as it is sorely used by the animals and nothing much remains but dirt. But it is worth this sacrifice for what it does for the rest of your farm. The period the animals are kept off the fields is traditionally called, "The Hungry Gap," for the animals are hungry for grass during this gap in their freedom, and like their wild counterparts, in their lowest condition of the year. In addition, the horses have already been working the ground, and the mares may have been carrying babies to near-full term. Gwyneth worked right up to the day before giving birth this time around. This is something working horses have long been doing, and it is actually good for producing uncomplicated births to work the mothers close to the day of arrival. This year, the hungry gap ended for us on May 21st. (A couple of days before this was when Gwyneth gave birth. Our first baby Clydesdale of the season, a lovely young filly.) The animals, some thin and even a bit bony from a too-long, if fairly flaccid winter, were eager as always to get out on the grass.  Gwyn and her brand-new filly break the Hungry Gap together. Gwyn and her brand-new filly break the Hungry Gap together. Every day or at most two, our herd is moved from one small pasture to the next, given only enough area to graze off completely in that brief period. The patch is not then grazed again until the grass has come back fully. This is called "Mob Grazing," and is the most efficient way to maximize the health of your pasture and the volume of grass, especially when it is a mixed herd doing the grazing, as different grazers eat the grass in a different fashion. Horses crop it down close and prefer shorter grass, for instance, while yaks and cows use their big tongue to encircle a swath of the tall stuff and pull it into their mouth. Our first paddock, the one we traditionally break the gap with, is a mixed aspen-balsam-spruce savannah, a small patch of considerably less than an acre. The animals love it in there, it is cool and lush, and they sure are a pleasure to behold in this setting. Soon their condition will be noticeably improved, and in no time they will be back in prime shape. |

AuthorHave a look at our "Education/Contact" page for info on the author. Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed