Across the old Roman Empire were scattered examples of the columbarium - "culvery" to the Cornish, "doocot" to the Scottish, "dovecote" to the English. These structures, some quite elegant, were all over Europe (at one time England boasted over 26,000 dovecotes.) They were the homes of pigeons. Most of these dovecotes were designed to hold between 200 and 500 pairs. They varied in design, but were in essence a brick or stone shed, stable or barn with portholes of a size to admit pigeons but not their predators, nesting ledges inside, and a door to admit humans. Some were rumored to have held up to 5,000 birds, and when the Roman Legions marched, these dovecotes provided a ready and self-sustaining source of food in the way of squab - a delicacy to this day. This was a brilliant and elegant system, a farm that farmed itself. Each day the pigeons would leave their cotes, scouring the countryside for seeds and waste grain. Interference was prohibited. Across the Great Plains are legions of abandoned granaries, many still in quite good repair. In them, by their own choosing, nest the feral pigeons, descendants of domestic birds brought to this continent hundreds of years ago, which in turn are the descendants of the wild ancestral rock dove, a denizen of remote sea coast cliff fastnesses. Were an enterprising person to outfit these bins with working doors and simple barred entranceways of a size to admit pigeons but exclude their main predators, the Great-horned owls, here would be a ready source of emergency food for the plains-dweller, a variation on the urban "food forest."  Wild-type Rock dove. Wild-type Rock dove. Pigeons have lived alongside man for thousands of years with the first images of pigeons being found by archaeologists in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and dating back to 3000 BC. It was the Sumerians in Mesopotamia that first started to breed white doves from the wild pigeon that we see in our towns and cities today and this undoubtedly accounts for the amazing variety of colors that are found in the average flock of urban pigeons. (And if you think they're dirty, you're looking far too closely at the bird as opposed to the city.) To ancient peoples, a white pigeon would have seemed miraculous and this explains why the bird was widely worshipped and considered to be sacred. Throughout human history the pigeon has adopted many roles ranging from symbols of gods and goddesses through to sacrificial victims, messengers, pets, food and even war heroes!  Miraculous they are. We keep a loft of pigeons at Thompson Small Farm. When I look at these birds up close, I am always struck by their marvelous beauty. Everything about them is perfect, sleek and sublime, nothing extreme. They are to me, the "a-priori bird," the bird that could be used as an example of "best in design." But looking at them as they interact in the loft is only the beginning of the enjoyment they bring. Along with ravens, pigeons are among the few birds that fly seemingly just for the pleasure of flying, and not just with some utility in mind. And well they should, as they, again like the ravens, and along with the falcons, are amongst the most superb avian athletes we know. They can fly for days on end if necessary, and have been known to average speeds of 125 kilmoetres per hour on their journeys. Morning chores around here are brightened by the spectacle of our pigeons on the wing, one moment mere specks high up and off to the horizon, and then close at hand, diving, twisting amongst the buildings, the wind shearing audibly through their pinions, their hues and forms marvelous against the backdrop of any sky, clear blue or against black storm clouds when they may appear as sparkling snow.  Thompson Small Farm pigeons at their loft. Thompson Small Farm pigeons at their loft. Pigeons are considered to be one of the most intelligent of birds, being able to undertake tasks previously thought to be the sole preserve of humans and primates. The pigeon has also been found to pass the ‘mirror test’ (being able to recognise its reflection in a mirror) and is one of only 6 species, and the only non-mammal, that has this ability. The pigeon can also recognise all 26 letters of the English language as well as being able to conceptualise. In scientific tests pigeons have been found to be able to differentiate between photographs and even differentiate between two different human beings in a photograph when rewarded with food for doing so. Pigeons and doves (which are two different words for the same group of birds,) are the only birds that dip their beaks into their water source and simply suck the water up, like a mammal - all others must "dip and tip" their heads. They are even easier to care for than chickens, being incredibly hardy (they often begin nesting in February, even in our climate, without any artificial heat source) willing and capable of caring entirely for themselves provided there is a source of forage on the land. And giving back almost as much as chickens and on some levels more. Perhaps if you are an urbanite frustrated by laws limiting your keeping of chickens, you should look into the legality of establishing a pigeon loft! Or better yet, keep both.

13 Comments

Hell is a strong word, but let me explain. The northern tier of North America's high plains, the region encompassing all of southern Alberta and southwest Saskatchewan and extending south in an eastward flexing arc all the way down to embrace the Texas panhandle and eastern New Mexico, hosts one of the most extreme climates on the planet. Where else on earth can temperatures fluctuate from lows of -40 to highs of +40 Celsius in course of a fairly typical twelve-month cycle? Oh, the soil can be rich indeed, depending on where you are, but add to these caveats of temperature the fact that it is windier here than an old man's yarns, drier than the humor contained therein and as unpredictably frosty as the fed-up wives who've endured years of such bullshit and you can see why this region could be considered hell, at least where vegetables and additional things, no doubt, of general tenderness, are concerned. Yet it is here that Andrea and I decided to start our CSA (have you read our "Dumber 'n a 'Possum" blog entry yet?) It was trial-by-fire, or for the more amphibious of bent, sink-or-swim, as we had jumped right in with both feet and no life-jacket. We needed a system of growing that could withstand pretty much the worst conditions nature could throw at a gardener anywhere actual soil occurred. The system we came up with we feel worked admirably, and we're confident it could be adapted by anyone, anywhere and yield gratifying results. We'll outline it for you here.  A fine high-plains April morning. Thompson Small Farm, 2009. Those barely discernible smudges are Clydesdale horses, about ten metres from the camera. A fine high-plains April morning. Thompson Small Farm, 2009. Those barely discernible smudges are Clydesdale horses, about ten metres from the camera. We start in late March or early April with a small greenhouse, which at this time of year, especially at night, will sometimes need some supplemental heat. We have provided this heat at intervals woodstoves piled around with rocks for thermal mass, electric and propane heaters. We like the stone-heaped woodstove method best, as it appeals most to our desire for self-reliance. Next, we either mix our own potting soil mixture or get some bagged stuff, and you can probably guess which approach we like best there. Out come the soil-block makers, an assortment of sized punches ala Eliot Coleman's "The New Organic Grower" (refer to our online store, which contains most of the reference works you'll need and which we, by their inclusion, endorse - including this one.) The punches create blocks of soil that hold together and negate the need for pots - a real blessing! We use the 2 inch size almost exclusively. You can pack a lot more plants into a space using the one inch size, but you need to re-pot them into two inch anyway, so why not skip this step? Seedlings, to make a long story short, are raised to optimal transplant size in these 2-inch blocks set into flats, about 40 - 50 per. While they're growing, we've been out there preparing the soil. This year, we've been feeding the animals on the garden space over the winter, in order that their ordure will generously anoint the land by spring. By doing this, you save on work spreading organic matter - it comes straight to the land from the horse's... it's there already. So this year, preparing the garden space will consist of harnessing the Clydesdales and driving them around the garden with a dual gang of spike-toothed harrows trailing, spikes in the flat position, to spread out the manure piles over the area. Next, we'll be turning the soil - not too deep - with a plow (horse-drawn, of course. If all you have is some machine, well, you'll have to make do with that for now. Hopefully you'll have animals of some description for manure, or you'll have to get your hands on some of that too, or better yet, compost.) The soil must be moist and friable for this step, but not too moist. Plowing is best done in the fall, so that the frost action can work on the turned soil over the winter, but if this system of "soiling the land" over the winter is used, you'll have to do it in spring, to work in the nutrients and organic material. That's okay. Just remember that when plowing is done in the spring, the disc-harrowing that always follows must be done immediately following the plowing to conserve soil moisture. So then, we disc harrow the plowed land. (If you plow in fall, the harrowing can wait til spring, and becomes the first tillage step.) Disc harrowing, back and forth and across and at all angles breaks down clods into a nice seed-bed, but the edges of the discs also compact the soil some, so we follow this step with some spring-tooth harrowing, or cultivating as some call it with this implement, to loosen the soil back up and give it loft. (We recommend "Implements for Farming with Horses and Mules," available through our store, for an understanding of equipment and the applications. It's the same sort of stuff you'd be using with a light tractor.) Now comes the making of raised-beds. Raised beds needn't have borders, and in fact this would be far too labor and infrastructure intensive for larger scale gardening anyway. Instead, they are just raised rectangles of soil, in our case about five metres long by a metre wide, by perhaps a hand-width or a little more high, allowing for from two to four rows of plants. In the past we've made these beds by hand, with a hoe, once the horses have helped us prepare the soil. It takes maybe fifteen minutes per bed if you've loosened the soil adequately, as needs be. If you can't get enough soil up into beds, get back in there with the spring-tooth harrow. This year I've added an application to our basic home-made stone-boat, a set of adjustable discs on a rear-mounted frame that i'm hoping will assist in making the beds with the horses doing the bulk of the work. The discs can be set wide or narrow, to heap the soil or make a planting furrow. We'll find out how this works! Raised beds are one of those steps that can make a night-and-day difference between small, stunted vegetables, and big proud ones. This is because the loosened soil, raised above the cooling thermal mass of mother earth, warms more quickly and allows for better penetration and retention of moisture and oxygen, not to mention root-growth. So, once your field is arranged into beds (leaving room to walk between and larger corridors for bring wheelbarrows and such out there,) let some time elapse, if you have the luxury (you won't some years,) so the weeds can get a start. Once they've sprouted, hoe them under. Hopefully there won't be too many, but this is a way of pro-active weed control, and it's added organic material as well. Now, a top-dressing of compost is in order, if you have it on hand, although it may not be necessary if you've fed the soil adequately as we've described. If you've got it, and you should have it, then use it. Just sprinkle a thin layer atop each bed - you don't need to work it in. Follow this with a thin layer of mulch - leaves, grass, straw, old hay, whatever. The mulch helps further with weed-control, adds further organic matter for soil building, and holds moisture. It's incredible, in fact, how much effect mulching has on soil moisture. It can spell the difference between needing to water liberally every day or two and just being able to rely on rainfall, or at the most, watering weekly. But it must be thin at first, as it also cools the soil, something you don't want to do in the spring, and defeating one of the purposes of the raised beds. You're now ready for your transplants. Before you bring your flats of soil blocks containing the baby vegetables out to the field, spend a few days introducing them to the full, unfiltered sun in increments, or they will be unhappy, or dead. It takes some "hardening-off" to get them ready for the full elements. Then you can take them out to the field with you. Mind-you, keep those bastards moist! They dry very quickly in the open air. Refer to your reference materials for spacing for the different plants, part the mulch and make a hole and insert the block. Gently squeeze it just before covering to break the form of the block and keep the roots from binding. Don't then pile-drive your fingers around the base like an eye-gouging street-thug as I've seen some guys do in order to anchor the plant. A little gentle tamping, like seating the tobacco in your pipe will do. Once a bed is planted as such, we then water each transplant in, regardless how moist the block is, and then we do it yet again, this time with a pressure-sprayer and a little fish emulsion added to the water. Just a squirt or two into the base of the little plant. We do the fish emulsion thing last so the previous watering doesn't flush the root-establishing nutrients down into the bed. Tuck the mulch back in around the base of the little plant. If you were somewhere pleasant, you could probably stop at this point. You are not somewhere pleasant, however, at least not for the sake of this instruction. This being the case, you're not done yet! And hey, even in a reasonable climate, the additional steps I am about to outline might just make you legendary. Give it a try, maybe in some trial plots. Anyways, now it's time to get out the 9-gauge wire and cut some hoops from it. You're going to push the ends of the wire into the ground to form semi-circular arcs over your beds at about one-metre (39 inch or so) intervals. They should allow for at least thirty centimetres (a foot) of clearance beneath them. You are in essence making a mini-hoop house over each bed. Over the hoops, you unroll a length of a product called "Agribon" or something similar - a gossamer-light fabric that admits both sun and precipitation, yet raises the temperature underneath by around three degrees Celsius, protects against frost, insect pests, and wind. (Wind robs plants of energy and stunts growth. And by the way, you can use this fabric in your starter greenhouses as well, draping it loose over flats at night to protect seedlings against frost.) You can use soil, rocks, sandbags, logs, or twenty-foot (about six metre) lengths of rebar to hold down the edges of the fabric. If you choose rebar, you can then use the same lengths at some other juncture to erect larger walk-in hoop houses when you need to. Soil is hardest of these choices on this material, but it doesn't last more than a couple of seasons in our climate anyway. We have lately gotten into the practice of buying this row-cover material in sufficient widths to cover two beds at a time, saving on labor. The hoops are still cut to width for one bed - they wouldn't be rigid enough for two beds, and you'd be tripping over them in the rows anyway.  Field layout, Thompson Small Farm. Some beds with mature plants are open, some are covered single-beds, and the wider arrays are covering two beds at a time. The corner of a second garden area is just visible in the background. Field layout, Thompson Small Farm. Some beds with mature plants are open, some are covered single-beds, and the wider arrays are covering two beds at a time. The corner of a second garden area is just visible in the background. You can open these covers to water, or water right through them, or better yet, it hopefully rains enough that you don't ever have to. As the season progresses, thicken the mulch layer to better hold moisture and suppress weeds. When the plants begin to bulge the fabric, open up the bed to the air. It's always exciting to see what's under there! Okay, there's our system in a nutshell. If you can't get a garden to grow using this method, you're probably an Eskimo and have many equally rewarding things to do anyway. So here I am at the kitchen table trying to get a better handle on the inner workings of the Canadian establishment with a copy Drisdelle's, "Parasites: Tales of Humanity's Most Unwelcome Guests," when around the bend of our drive comes our neighbor Harold in his pickup. Harold needs help with a task he can't handle on his own, and so off we go. We don't engage the term "bovine" too often as a compliment, remember, and here we have a Hereford lain on her side with her feet on a vaguely uphill grade, and due to the insurmountability of her balloonish midsection, is now powerless to get up. She'd been there for some time, it would seem, as evidenced by the brown pond adjacent her hoop, in which she had thoroughly plied her tail. (However this turns out, stay back from the tail, I remind myself.) "Oh Lord," was one preliminary thought, "She's having trouble birthing and one of us sure as hell will soon be up to our shoulder in her wildebeest trying to turn the calf!" Her tail a paint-brush. Immediately followed by, "Why do all cows seem to live in a perpetual state of diarrhea?" and then the revelation, "It's not enough to make responsible decisions in choosing for yourself only those proper animals that can birth naturally when your neighbor insists on keeping up the tradition of raising only those animals we've thoroughly screwed..." when, praise-be, it became evident that while pregnant, this was not the true nature of her predicament. She was simply defeated by her own preposterous design. Lucky it was us and not coyotes coming to her aid. I am sure, in fact, that if we hadn't been there to lend a hand, this would have been a scene to be immortalized on canvas as "Bessie's Final Gesture." Serving perhaps as a symbol for where the process of domestication was taking us all - a bloated carcass to be eaten alive by scavengers. As it turns out, the fix is embarrassingly simple. Harold applies a lariat to both her hind feet. We heave until she's rotated 90 degrees, (thankfully the ground is slippery with snow and less pristine substances,) head now upslope, such as the slope was. She gets up and walks off, as if she's only been napping a moment or two. Domestic cattle were established in western North America mostly by English elites of the then prevailing Empire in order to better provide for an insatiable appetite amongst the British aristocracy for beef. Big money cleared all hurdles, and with this backing, the cattlemen of the west carried mighty political clout, the remnants of which, despite the cattle industry being in severe present peril, remain to this day. Observe single-family holdings of vast estates here in the west, acquired and held on to for a veritable pittance by the standards of today due to this history of partisan politics. And so worked, and works - barely - the mechanism by which an animal far from optimal for its situation became every bit as sacred to westerners as it is to the Hindu, nevermind that we eat it. Anyways, to hell with cows, and pity the poor cowboy tending these squalid hordes. Here's a better solution:  The yak was introduced to North America by way of Canada, and we can thank naturalist and artist Ernest Thompson Seton for this. Seton presented the idea that yak would be the perfect animal for the Canadian plains to Lord Albert Earl Grey, the Governor Central of Canada. Lord Grey presented Seton’s idea in a letter to Lord Elgin, the Secretary of State for the British Colonies. In his letter Grey states that the Premier of Canada, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, had already requested a formal report from Seton. The project was given the thumbs-up and the original animals were acquired from Herbrand Russell who was the 11th Duke of Bedford, President of Zoological Society, savior of Pere David’s Deer and who had a herd of his own yaks at Woburn Abbey. In 1909 a small group of the animals arrived in Brandon, Manitoba for research purposes. The answer to the question is this the ideal domestic animal for the Canadian plains is of course, "No," the bison was and is the ideal animal for the Canadian plains, but you know the story there. The yak is certainly second-best, and when you factor in ease of handling, they have bison beat. The yaks failed to thrive in Brandon, low elevation being blamed. They were moved to Banff, did much better there, and by 1919 a sizeable herd was the result. Animals were then moved to Wainwright, Alberta where the original question somehow became twisted out of shape thanks one can imagine to political meddling by the already deeply-entrenched cattle industry. The question became, "Can the yak be used to improve cattle, can cattle be used to improve yak?" The answer of course was again, "No," you breed them together and you get a critter that performs poorly as both a cow and as a yak. So the project was abandoned as we turned back to our cows. On the plus side, there were now yaks in Canada, in North America. Now, on to the details. Who better than the International Yak Association (IYAK) to further illuminate the superior qualities of this "Cow that should have been"? "The strength and value of the yak comes from its amazing versatility. Try to find an animal that can fill so many roles. Their fiber or wool compares to the finest fibers in the world and is enjoying growing international interest as companies like Khunu and Shokayintroduce the work of the indigenous peoples of the Himalayas to amazing yak fiber products. Even Newsweek is jumping on the yak wagon! Yak leather is THE Premium Leather for Ecco's top lines not because it is different but because it allows them to produce a superior shoe. According to Ecco's testing, yak leather is up to three times stronger than traditional leathers allowing them to produce lighter and longer wearing shoes. The health benefits of yak cheese are becoming famous world wide. Yak meat is becoming a favorite restauranteurs, chefs, health conscious foodies, and folks looking for a delicious alternative to everyday beef. As a companion animal, you will not find a more intelligent and hard working partner. "Yak down is the softest yak fiber and is the undercoat the animals grow for insulation in the colder months. It is shed in the spring and is wonderful stuff for woven and knitted garments. The down is a short fiber--about 1-1/2" long with some crimp, and it may be challenging to spin unless it has been carded into a roving. As you can see below, the fineness of the yak down fiber could be equated to merino wool or cashmere, and close to qiviut (musk ox down). Yak down does not have the lanolin that makes sheep wool greasy, so you don't lose much in weight when it is washed. The other fibers are medium length (about 2-3 inches) guard hair that is usually mixed in with the down when it is combed out, and then the long, really coarse guard hair that creates the yak’s “skirt”. A rug woven from this guard hair would wear extremely well. "The amount of down fiber on the yak’s back may vary between animals, but it has been shown that the cooler the climate and longer the colder weather lasts, the more dense a coat of down fiber the animal grows. The density of the down coat is greater in calves than adults because their bodies have not built up the fat and hide thickness to protect them from a harsh, cold environment. The denseness of the down coat usually decreases with age as the animal builds up more subcutaneous fat and its hide becomes thicker. "Yak meat's sweet, juicy, delicious flavor is never gamey and is not dry unless overcooked. Although very lean, the juiciness and flavor of yak meat comes from its unique mixture of fats that are low in saturated fats, cholesterol and triglycerides. Yak is a red meat that offers heart patients a new opportunity for fine dining and offers athletes a diet exceptionally rich in body building proteins, minerals, vitamins and the right fats for building muscle mass and good health. This healthy and delicious meat product is a driving force behind the yak’s value and success as a profitable livestock enterprise. "Yak Milk, contrary to legend, is not pink but yak butter's legendary status is well deserved. Yak butter tea is the comfort food of the Himalayas. Yak milk is rich in butterfat at around 6% to 11% and this makes it perfect for yogurt, butter, and cheese. No animal has such a history of carrying heavy loads in extreme terrain. Their sure-footedness makes them the only choice for the world's most famous mountain climbers and folks just looking for a some time away."  Baby Rose, a calf from this year. Baby Rose, a calf from this year. We would add a few anecdotes here. People interested in sheep but worried about the predator problem (amongst other problems with keeping sheep,) might consider the yak instead: woe to any coyote who would make lunch of a sheep who tries to do the same to a yak - they have little tolerance for such nonsense and he'll just as likely end up skewered! Coming from dry areas, yaks utilize moisture better than cows. Their droppings are not a perpetual filthy mess like a cow's, but rather more like an elk's. Also, they don't swarm around waterholes, streams, or rivers all summer as cows do, destroying the ground, the riparian habitat, and fouling the water. They eat about 1/2 as much as a cow pound-for-pound, allowing higher stocking rates, if that's your goal. They also eat a broader range of vegetation. On our old place they virtually eliminated kochia, a noxious weed nothing else would touch, and put a dent in the snowberry invading the native grasses. They are calmer than cows, easier to handle, and as our friend Ken at Rafter K 2 Farms, a man who has raised both cattle and yaks reports, this is likely due to the fact that there is no comparison in intelligence between a yak and a cow, nor in health issues. They tend to birth easily, naturally, without assistance. We appreciate also that yaks are not prone to rending the otherwise peaceful country air with penetrating, moronic noises ala the cow. A relatively soft and infrequently uttered grunt is their only call. Finally, yaks are picturesque. They seem to fit the wild landscape, to look appropriate there, where cows always seem to detract from any scene beyond the dairy fold. They are much like bison this way. In fact, we have often reflected that a yak can be viewed as a small bison that will make friends with you rather than try to kill you. We are very happy to have a growing herd of yaks again on our place. Aside from their many uses, they lend us a sense of well-being by their very presence. And hey, maybe things are coming full circle: yaks now have at least token backing from the new generation of British aristocracy. When the young Royals were here recently, guess what they dined on? "Are we headed for Renaissance or Ruin? The future is up to the individual. When the human spirit rises, everything changes!" - Gerald Celente

Gerald Celente, founder of The Trends Research Institute in 1980, is a political atheist. Unencumbered by political dogma, rigid ideology or conventional wisdom, Celente, whose motto is "think for yourself," observes and analyzes the current events forming future trends for what they are – not for the way he wants them to be. Celente has earned his reputation as "The most trusted name in trends" by accurately forecasting hundreds of social, business, consumer, environmental, economic, political, entertainment, and technology trends. I recently had the opportunity to however briefly rub electrons over the radio with this man, Celente, one of the folks I have been keeping my eye on for some time, in attempts to make sense of the general unraveling of things. Donna McElligot of the CBC has been growing some big stones, as evidenced by inviting this man on her call-in show, "Alberta at Noon." For Celente tells it as it is. Far be it from him to deliver the normal mandated mainstream pablum most of us are fed by an establishment that would have us all their infant call-children. I was hoping some spare grey stuff might come spilling down the line from his brain-box and anoint me. He did not disappoint. He had plenty of spare wisdom for us all. Celente is, as we just mentioned, a "political athiest," like myself. Someone who sees Big Politics as a spectacle increasingly removed from the real world, a self-serving sideshow much like the practice of law has become, law having not coincidentally spawned the overwhelming majority of our leaders. Like the legal process, an impediment more often these days than not, or at best, just another business like any other - a casino, say, or an escort service. At worst, an infestation. I'm sure our First Nations, a people who'd been doing quite nicely managing their own affairs sustainably for millenia, viewed it that way once upon a not-so-distant time, if not still. A political atheist is someone who may remind you, "Don't cast your ballot on a dung-heap and expect not to be delivered a shit-beetle." A political atheist is someone who refuses to lend legitimacy to illegitimate people and their illegitimate processes, created by themselves for themselves, through willful participation in that process. A political atheist is someone who recognizes that much as we'd like to be able to make the monsters go away through the simple act of dropping an "X" into a box, free then to slip back into peaceful slumber, it doesn't work that way. Not for long, anyway. Clearly not now. But as this is the case, how then will it work, "going forward" as we so like to say these days? It's an understatement to point out that we need to know this. I was driving into town to get a thousand pounds of oats when Celente was announced as guest of the call-in show. Appalled at the idea that we might blow this rare chance to cut through the dryer-lint of usual mainstream discourse, that the discussion would be steered towards such trivial matters as the "unfair portrayal of the Tarsands," or worse, "what do you think of the fact that we are golfing in Alberta in February," I got right in there to see if I could not help massage things towards the much-needed wake-up call I knew this man, given this opportunity, could deliver. I needn't have bothered. He needed no help from me. Celente's message for us was both ominous and inspiring. Here are the highlights:

Celente pointed out that those who didn't see our current crises coming were looking to the wrong people, to the specialists lacking in necessary scope. I would concur. It seems to me a given that we not listen to any economist lacking a broader education in the workings of natural systems or the history of human civilizations, for example - they are not equipped for their job. If you've been doing your digging outside the mandated media placed within our most convenient grasp, it's pretty clear where we're headed, and has been for generations. This was one of the primary motives behind our founding Thompson Small Farm, and now The New Farmer School. For as Celente, a martial black belt trainer, points out: "The first rule of Close Combat is to attack the attacker. Action is faster than reaction. The same holds true for the future. You know the future is coming … attack it before it attacks you." Dusk or Dawn? It's your call, and mine. How will it be made to work, now? It will work like this: buy local, augment your skill-set, embrace your neighbor, nurture your own community, make your own decisions, know your farmer. You've heard no doubt of "The Land of Cotton." Well, I come from "The Land of 'Possum." It wasn't always that way in Lincoln County, Ontario. I was fourteen years old (although I didn't know it at the time,) when classmate Bollard Kluk came to school reporting that he had seen one of these improbable marsupials. No one believed him at the time, in fact, most of us thought he had simply seen a pale rat. (Bollard was blind in one eye, so naturally everything he saw looked twice as big.)

Nonetheless, it was no more than a couple of years later and they were showing up everywhere, town & country. Now, a 'possum is a very stupid animal. It has the most teeth of any mammal, but a brain about the size of a tomato seed. It is so stupid, that even with all those pointy teeth, it can't be induced to bite. Believe me, I've tested this theory. (I know, that's stupid too, but in my defense, may I offer the spectacle of the Lion Tamer.) It gets so worked up not knowing how to use its teeth, that instead of biting you, it just passes-out. It is so stupid, it doesn't cross the road, it walks right down the middle. (I've actually seen it walking down the on-ramp of a busy four-lane.) It is so stupid, that even with perfectly good countryside available to it on all sides, it is just as likely to choose to live in the city. (Couldn't resist that one.) It is so stupid, that when I take it into the elevator to visit my father, it doesn't know how to use the buttons. It is so stupid, it left a perfectly decent climate like Virginia to come to Canada. Which brings me to my point. Stupid as the 'possum is, when he arrives here in Canada, he sets up his livelihood such that he has the choice of whether or not to get up and go to work on any given winter day. Right about now, with the mercury dropping to the -40 range, i'm thinking about this. You see, I have set myself up such that even if it were hailing anvils, if it kept up, sooner than later i'd have to venture out in it. What bothers me is this: am I therefore Dumber'n a 'Possum? What is with that damn Arctic, anyway? Why can't it just stay put? What business does it have, how little manners does it possess, that it see nothing amiss about to sliding right on down here into the middle latitudes? It's ridiculous. And being a man, and not a 'possum, I have been spending a fair bit of time out in this frigid insubordination. The perversity of livestock is such that it is when the conditions are the worst that they most require your assistance. How do our livestock compare to 'possums? The chickens don't come out much in this, and their egg-production drops precipitously. (Last week we were up to over 50 eggs a day, pretty good for mid-winter, now we're down to a dozen.) The pigs lay like sardines in a tin, nestled in a deep bed of straw. We've built a low ceiling, or pig-lid, over their bed in the corner of a calf-shed, about as high as their backs, and layered also with straw on top. This sort of thing greatly decreases the radiation of body heat into the upper reaches. This is why deer - and smart woodsmen - locate their cold weather camps beneath overhanging evergreens. The pigs, near-naked as they are, so almost human, so like my Uncle Adrian in the U.K., don't seem to suffer given these basic living conditions. The yaks are built for this. They get a little more serious about food, but being from high latitude Mongolia and other nasty places much like ours, they're still pretty mellow. Not so the horses - mellow that is. They get tough with each other when it's cold. In fact, you could tell how serious-cold it was just by watching their behavior at feeding time. When the Arctic, the lousy, filthy Arctic, the kick-you-when-you're down Arctic, the sneaky, conniving, double-crossing... When the Arctic slides down off its proper polar perch, the horses get serious about food, and the hierarchies are strictly enforced with bites and charges and flying hooves. Beyond this, though, I think they are even tougher than the yaks. While on occasion we have had a yak suffer from frost-bitten ear tips, none of the horses has ever had this issue. The milk-cow, on the other hand, is a wimp. She stays inside her stall in the barn throughout this transgression of the you-know-which part of the globe, and she wears her insulated jacket to boot. Cows are smarter than chickens, but not by much, so of all the large animals they adapt the best to confinement. There are no 'possums here. Anyway, who cares - I go out to feed the animals in the gloaming. It's a balmy -26. I am glad and impressed that the automatic waterer remains in operation. (The heated pump from the well is not.) I siphon some into a bucket to top off the chicken's water now put right inside their henhouses - they don't drink enough in this weather otherwise. All the chickens are in, save three Isa Browns. This is the variety that has been engineered to lay brown eggs in the battery barns. They are 'possum of the chicken world. There is nothing whatsoever wrong with their eggs, once the Isa is removed from the indecent conditions and food regimens of the big barns, but there is definitely something wrong with the chickens. They are the first to die under harsh conditions like these - or any conditions - they just don't hold up as well as the heritage breeds. They also seem to be instinctually challenged. In the summer, they linger about into the dusk, long after all the other breeds have gone safely to bed, risking the fangs of predators that the others understand, oblivious. And now, on this frigid night, here are three of these idiots, roosting on the ground outside. I go back to the house, and bring out an old copy of "Wild Animals of North America." I open it up to the 'possum section, and show them a particularly un-flattering illustration. I give them a good long look. I get no response. Disgusted, I pick each one up and put them in the warmth of the hen-house, with the responsible poultry. It is now full-dark, clear, and the temperature is dropping fast. Heading back to the house, I reflect as I always do, how amazing it is that no matter how cold it is, once you are out doing your thing in it for awhile, you cease to mind it anymore. It's actually quite refreshing. I am not so dumb as I am, after-all. And one thing I didn't point out about 'possums is that when winter comes and they grow their coat out, they are actually quite beautiful. When you raise your own chickens from a mixed hatchery order, or as we mostly do, from chicks you hatched yourself, you eventually run into the problem of too many roosters. The ideal ratio is about 1:12 roosters to hens. You could go around doing counts, but that's hardly necessary, if you're hatching and raising your own birds. You'll know when you have too many roosters - the farmyard dissolves into avian chaos.

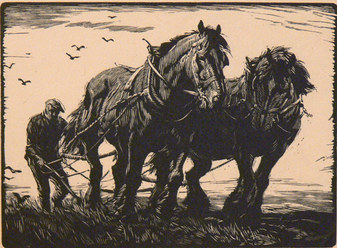

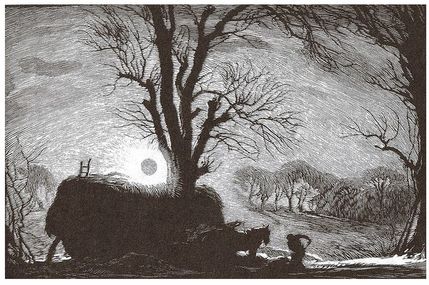

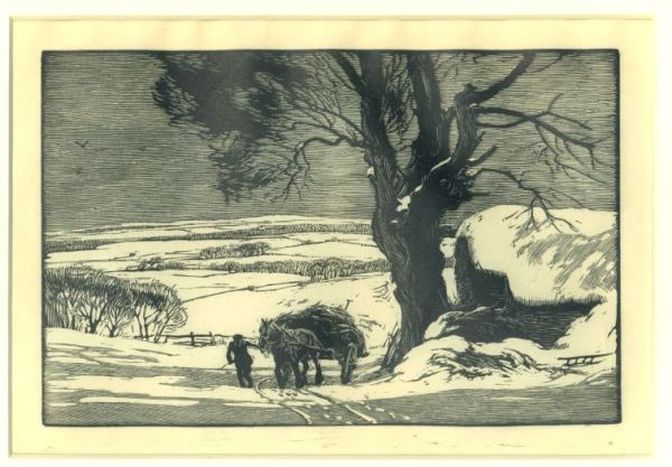

Every year at some point it happens around our farm. In doing the daily rounds you become aware that the ambiance, the energy about the place, has ceased to be one of balance and peace. And it doesn't take long to pinpoint the reason: everywhere you look there are newly matured roosters in frenzied pursuit of hens, sometimes two or three on one, and more roosters pursuing the pursuers. Crazed cackling fills the air with little respite. The hens are understandably stressed and egg production begins to drop. The roosters are stressed too, with an adversary at every turn. There's no way around it, it's time to "cull" - read: kill - a bunch of roosters. So we killed roosters this past weekend. Killing things is never particularly pleasant, being the very definition on some level of excess violence, even when done humanely. Yes, you do it in as instantaneous and stress-free a fashion as you can devise, but the end result is nonetheless the termination of life. Which, for us, always leads to much reflection and discussion, before, during, and after. I think one of the things that would shock most non-farm folks should they begin farming, and on the other hand, one of the most valuable lessons most folks today are not receiving, is the amount of baseline violence that must go on just to sustain life and maintain order. Soldiers like to remind us of this. And if the farm is indeed a little ecosystem symbolic of the larger workings of the living earth, then i'd have to say they are correct, at least in principle. For sooner or later (probably sooner), if you are farming as farming is meant to be done, in a mixed and sustainable fashion, you are going to have to kill something. It may be an old breeder that is suffering, it may be an injured animal, it may be a meat animal, it may be a predator, it may be rodents in the vegetables or the granary. There is going to be killing to do. Sometimes, it becomes a daily ritual. (By the way, please note we aren't trying to dupe you, morally swindle you, to evade accountability with sanitizing terms like "harvest" in this post. Crops are harvested. Animals are killed, slaughtered.) There are those who argue that this is one of the problems with farming, that it pits man violently against his fellow creatures, against nature, forgetting that life itself pits pretty much all creatures against their fellow creatures at regular junctures, that this is nature, and that in fact what ensues is actually preferable to the sorts of situations that develop when not enough of this sort of baseline violence occurs. Things like disease and starvation and neuroses and psychoses due to overpopulation... and trouble in the henyard. This time, I chose to use the scoped .22 rifle for the task. My usual technique was to try to walk calmly amongst the birds with a long stick, lashing out swiftly at the right moment to stun the bird and then quickly slitting its throat. I reasoned that this was less stressful than catching them and hanging them up and otherwise terrorizing them. But sooner or later they catch on, and panic ensues. So I further reasoned that if I just strolled about calmly with this accurate little rifle loaded with the lightest and least dangerous rounds available for the task - the .22 "short" - I could "reach out" from a non-invasive distance and deliver the coup-de-grace without producing any panic whatsoever. This proved to be largely correct in practice. I would aim for the head, and if my aim was true, Andrea would then slip smoothly in with a sharp Bowie and slit the throat to make sure of the outcome. The other birds just seemed curious, or puzzled, although some of the hens went immediately haywire, attacking the rooster in his throes and pecking savagely wherever blood showed. (Maybe these were the ones with a score to settle.) And as anyone who has ever done any amount of killing will tell you, sooner or later things do not go entirely smoothly. This is inevitable. Your job then is to act quickly and decisively to reduce any suffering. This may sound unpleasant, and it certainly is. But we have found there is nothing like accepting this responsibility for arriving at a deeper understanding of our basic contract with life, the breach of which we enter into at immeasurable peril to ourselves and other life forms. We expect it is as true in this case, as in so many others, that we lose far more than we gain by "outsourcing" a vital act. We killed thirteen roosters in all, gutted them and put them in the freezer for later stewing (they are delicious!) The guts went to the pigs. I was happy for the firearm. Those opposed to firearms might do well to contemplate themselves on a farm, tasked with, let's say, killing something large - beyond a rooster - perhaps a pig or a steer, with something other than a gun. A knife or a spear, perhaps - maybe a club. Your odds of delivering that animal as humane a death as possible have just dropped precipitously. At any rate, we're glad the task is done. Perhaps we value the peace that has been restored that much more, relative to what was necessary to maintain it.  George Soper was an artist of no formal training who lived from 1870 to 1942. His artwork captures the heart and soul of an era that only exists today (and miraculously at that) in the scattered Amish communities and a few other nooks and crannies of what has become an otherwise machine dominated world. He rendered a mostly bygone era then, and did it like no other. It is no accident that he dearly loved the working horse, as this animal was the heartbeat of his day, as it was of most of the days of civilized man.  "Carting Hay." Soper was something of a wildlife conservationist, and when he died, his home on four English acres reserved for wildlife habitat was kept on by his spinster daughters, Eileen and Eva, who also kept up his conservation work. When the sisters eventually became old and ill and entered a nursing home, a family friend, Robert Gillmor, was invited to sort out their father's artwork, most of which had never seen the light of day. Gillmor had no idea he was about to unearth the largest selection of drawings and paintings of horses at work, ever.  "Winter Sun" c1938 What makes Soper's depictions of working horses and their people so arresting is the fact that these are no works of the imagination - Soper was there on the scene, tools at hand, recording what he witnessed for posterity. I for one am very thankful this gifted man took the time to do so, as much so as I am his incredible artwork came to see the light of day, for all to enjoy. "George Soper's Horses" is now available from our General Store (click link tab at top of page.) We heartily recommend it. Chris Beetles Ltd. of London, England took over the Soper Estate on behalf of the Artists General Benevolent Institution (AGBI) in 1995. Visit the gallery online at WWW.CHRISBEETLES.COM.

So we finally got the old bobsleigh to the new location from the old farm, with help from our friend Kris Vester of Blue Mountain Biodynamic Farms. I was glad it was still there. Some so-and-so stole my anvil from the Quonset, you see. I hope he dropped it on his foot. In fact, I have been accosting everyone I see who has a limp. "You stole my anvil!" From the reactions, I can tell so far the folks have been innocent. Maybe some anger issues.

Loading the sleigh onto the trailer went well until we started talking about how well it was going, then it quit going well. But these things never do go entirely smoothly. You get used to that. We had a good time. I bought Kris dinner on the way home. Cheesies. I am using the big sleigh to start getting the horses back in shape this winter. Horses are like athletes, or sometimes, like most of the rest of us. Then you have to get them back to being like athletes. When you have four big horses to give a workout to, and short winter days, it helps to have a big bobsleigh and some heavy snow. This day we just so happened to have both on hand. To save on time, I decide to exercise them all in one big batch of horses, three-and-a-half tons or more of equine. The hitch is called a "four abreast", that is, four across. Clydesdales, left to right: Emma the blue roan broodmare, Raven the black Clydesdale/Percheron cross with "four whites" (feet,) Sarah, blue-roan first daughter of Emma, and Gwyneth the bay sabino. Four horses hitched like this are a handful at first, but they get into the swing soon enough and it's not so bad. The lines are a little slippery in my hogfat greasy gloves due to the wet leather in the strong Chinook. And the hogfat i've been feeding the nuthatches and woodpeckers . Just as with loading the sleigh, things go very well today in the driving of the horses - until they don't. Today was in fact a lesson in why you want to have well-trained horses before you ever hitch them to anything. We're passing a little close to some small trees, when Gwyneth on the far right suddenly darts around the far side of one of them. Of course, this doesn't work so well, all the horses being attached to each other as well as to the sleigh. A situation like this with horses that aren't really ready to be hitched and aren't fully trusting of you can be a full-blown wreck - all proverbial hell can break loose. But our horses don't get driven until they've demonstrated they're trained well, and knowing who their best friend is to boot, and this is the sort of situation where this cautious approach to training pays off. "Whoa!" I intone, and they all immediately do. What would have been panic in the wrong horses was merely a brief confusion in these girls, with Gwyneth sitting on her bum in the snow like a 1900 pound dog and simply going inert, ditto the other three, only still standing. They trust that when things like this happen, i will make things right, and so I do. That's my job, as far as they are concerned - they work for me because they know i'll make things right. That's the deal between us. "Just rest girls" I tell them, and knowing these words from long days in the fields, they do, letting their heads down and blowing out their stress through now relaxed lips. I unhook Gwyn's lines and tugs, move everyone forward just a bit by their bridles to clear the young aspen, and hook back up. Gwyn's nuzzling me now, opportunistic for some affection, the other girls just standing, their breath already slowing again. It was just another minor bump in the day's road for us all, no big deal, she's letting me know. I'm very proud of them all and their ability to remain calm in times of trial, and I make sure they understand this. I am so often proud of them, and so grateful for them. Then off we go again, dashing through the soggy snow on a four-horse open sleigh, another circuit around the back fifty. All's well that ends well. They'll be hardened back up in no time. |

AuthorHave a look at our "Education/Contact" page for info on the author. Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed